The Political Sport

Politics - “the activities associated with the governance of a country or other area, especially the debate or conflict among individuals or parties having or hoping to achieve power.”

Nazi Germany competing in the 1938 World Cup.

In 1936, Germany hosted the Olympics and, while the selection of Berlin to host the Games had happened before the Nazi rise to power in Germany, Hitler and his propaganda team saw it as the perfect platform to promote their ideals and vision for the world. As Mike Twardy put it, “for Hitler, the 1936 games were a pageant for Nazi propaganda.” Many in the United States called for our country to not participate, due to the escalating persecution of Jews in Germany, but the American Olympic Committee decided to send our athletes to the competition. And while many remember the impressive performance by American Jesse Owens, many do not remember that Owens ran in the 400 meter relay because a Jewish American athlete was not allowed to participate at the Olympics, out of fear of offending the Nazi hosts.

Sport is, and always has been, political. That’s because humans create sports, play sports, support sports, fund sports. To be human is, to quote Aristotle, to be “a political animal.” Everything we do is a political act, whether we are conscious or unconscious of it. From where you buy your coffee, from how you worship (or don’t), from where and how you live - every bit of that is political. It’s certainly not a vote or a campaign slogan, but each and every action we make is a decision about our views on our society and the way we think it should operate. And yes, the sports we consume, the teams we support, the leagues we fund - all of those are political acts, regardless if we desire to be apolitical or not.

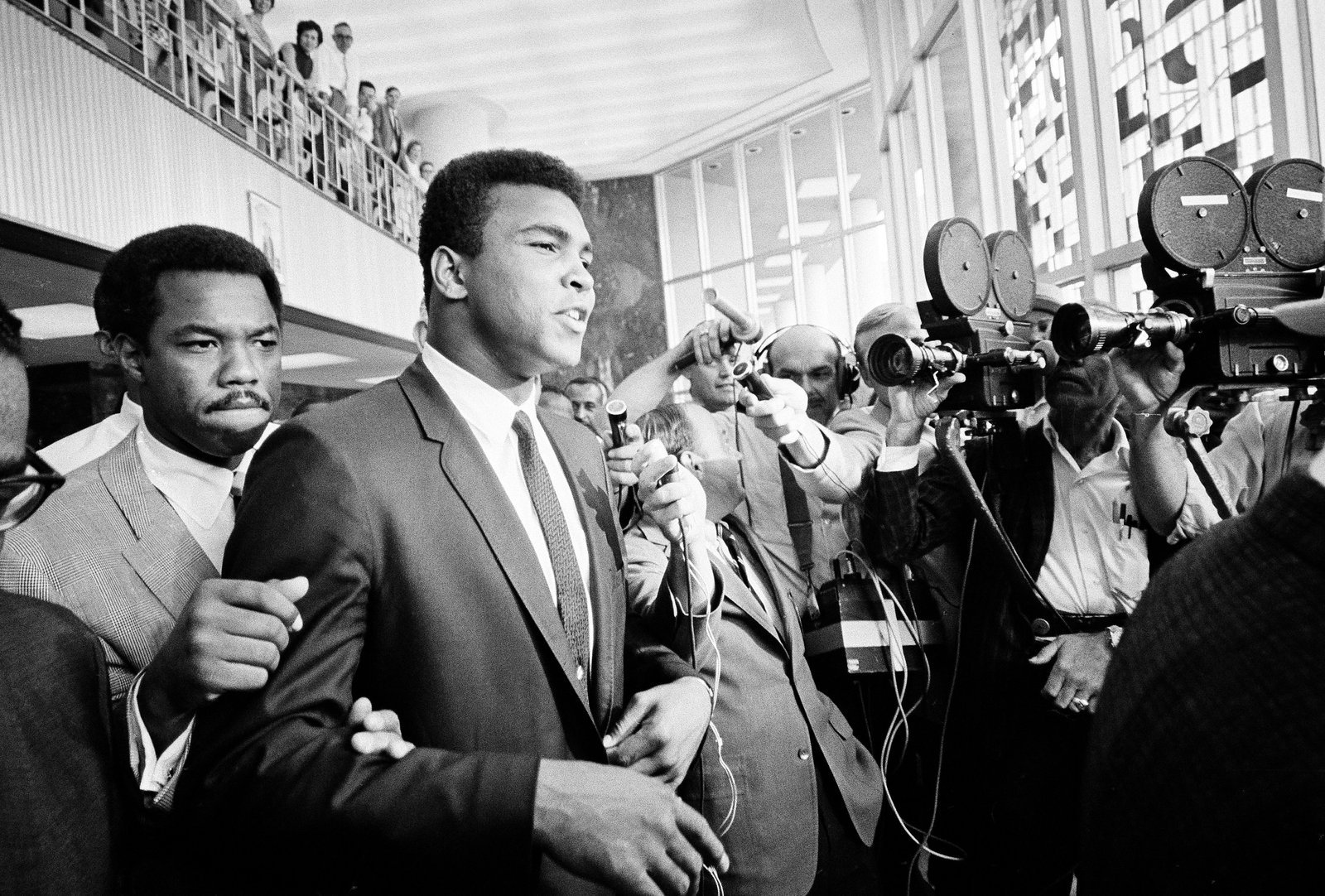

Sometimes, like the 1936 Olympics, the negative political impacts are much more obvious and unavoidable. But sports has also been used for societal good. Consider the actions of Muhammad Ali in the 1960s, using his platform as the “greatest ever,” to make stands about race, war, and American society. He intertwined his political opinions with his sporting performance and is universally lauded now. However at the time, David Susskind, a popular talkshow host, publicly expressed his disgust for Ali: “I find nothing amusing or interesting or tolerable about this man. He’s a disgrace to his country, his race, and what he laughingly describes as his profession.” This flies in the face of history’s judgement of the man, but iconoclasts are often hated in their own era. Telling someone to “stick to sports” is not new.

Soccer has been expressly political in history from its inception to the modern era. From its founding as a “gentleman’s game” that banned women from participation, the game was political. Macon Benoit, in his 2008 article, “The politicization of football: the European game and the approach to the Second World War,” discusses how in the 30s and 40s, soccer became hyper political as an agent of international relations, as a source of political propaganda, as a tool of public pacification, and as a medium of popular protest. All of those descriptions of the sport continue to apply today. Soccer is not simply sport, it is political expression.

In no country is this more obvious than in Spain. Spanish football has always been one of the most strikingly political in the world. The two most famous clubs in Spain (one could argue in the world), constantly in competition for the La Liga title, are stand-ins for Spanish political perspectives. Real Madrid, founded in 1902 as Madrid Football Club, was renamed in 1920 “when Spain’s then-King Alfonso XIII granted the team the right to use the term “real” – meaning royal – in its title and a royal crown in its emblem.” FC Barcelona is based in Catalonia, a part of Spain where “many people regard themselves as politically and culturally different.” When these two clubs battle, it is more than simply a game of football. It is a political battle around identity, independence, and national pride, taking place on a soccer field. The clubs are expected to, aside from win the title, align themselves with the political perspectives they represent.

In 2016, USWNT star Megan Rapinoe kneeled during the national anthem, in support of Colin Kaepernick’s own kneeling during NFL pregame ceremonies. Rapinoe was outspoken about why she was kneeling, refuting critics who used patriotism and disrespect of the military as criticism. She consistently highlighted racism in the United States as the reason for her kneeling. “When I told journalists I was kneeling to draw attention to white supremacy and police brutality, a lot of white people took it incredibly personally. I found this bizarre. It wasn’t their fault as individuals that slavery happened, but it was the responsibility of all of us to address it.” In response to Rapinoe’s actions, U.S. Soccer released a statement that, in part, said “we have an expectation that our players and coaches will stand and honor our flag while the National Anthem is played.” Rapinoe continued to kneel, regardless of the federation’s complaints. Soccer is political.

Kenan Malik, writing for the Guardian, discussed players kneeling before matches to protest racism and summed up the political tie to sports. “Most of us want the humanness of sporting achievement to transcend the immediacy of its political and social environment. Few want sporting tribalism to be consumed by political divisions. Nevertheless, most recognise that sport cannot be detached from its social grounding. Nor would we want it to be. For it is that grounding that imbues sport with much of its meaning.” Telling athletes, writers, and your friends to “stick to sports” does not remove the politics of the games we love. Politics underlie everything in our lives, ignoring those ties is also a political act.

We have to keep #Politics and #Political messages out of every level of our Game! PERIOD!

— John Paul Motta (@JohnPMotta) March 31, 2022

And that brings us full circle to why this article is being written in the first place. I have tangled with John Paul Motta, President of the United States Adult Soccer Association, on many issues on social media over the past 4 years (before then, I was blissfully unaware of the man). We have clashed enough that he has blocked my personal account on Twitter, though he follows the Protagonist account. Undeniably, we have incredibly different political perspectives, though I appreciate his dedication to growing the game of soccer in this country.

I do not know the specific reasons for Mr. Motta’s article-inspiring social media post, but generally those who argue against political expression in sports are arguing against A CERTAIN political expression. They do not complain about the National Anthem being played, the military flyovers, or the nationalistic expressions that dominate international sporting events. No, they fight against acts of protest against societal norms. They condemn the political points of the Muhammad Alis, the Colin Kaepernicks, the Megan Rapinoes. And so, to condemn those acts of protest, they decry “politics in sports.” However, pretending that we can remove politics from our sports is a bridge too far. Sport is political, as it reflects our society and our humanity. Soccer is inherently political. Denying that is either hypocrisy or idiocy.

- Dan Vaughn