The Post War Sports Boom and the Birth of the North American Professional Soccer League

After the end of the Second World War, the U.S. began to transition from a war-time to a peacetime society. One immediate reaction to this change was an enormous surge in interest in professional sports. New leagues sprang up to satisfy this need and to challenge the more established leagues. In late 1946, the All-America Football Conference and the Basketball Association of America both played their first seasons as direct competitors to the National Football League and the National Basketball League respectively. The sport of soccer also saw a rise in interest and, earlier that same year, the North American Professional Soccer League began play. [Editor’s note: The league is now more commonly known as the North American Soccer Football League.]

April 20, 1947 Chicago Tribune Article.

The league was the brainchild of Fred Weiszmann, who played football in his native Hungary as a youth. By 1945, Weiszmann was a restaurant manager and owner of the Chicago Maroons soccer club. But, he had grand aspirations for soccer both in the U.S. and worldwide. Weiszmann dreamt of an international soccer league where the top teams from each region would play each other in a super league. With Phil Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs, as the Maroons sponsor, Weiszmann applied for membership in the American Soccer League, the only real professional soccer league in operation. The ASL denied the club admission but, in November, gave Weiszmann tentative permission to launch a Midwest Division of the league.

Weiszmann began discussions with midwestern amateur clubs about forming the new ASL division, while, at the same time, the Inter-state Professional Soccer League, another proposed regional league, was in the works. While the ISPSL never materialized, Weiszmann was able to raise $75,000 to launch his new endeavor and gained rights to all the open dates at Wrigley Field for his club.

In January 1946, the proposed ASL Midwest Division announced it had a roster of teams: the Maroons; the Chicago Vikings; Morgan Strasser of Pittsburgh; and John Inglis of Toronto. All of these were successful amateur clubs in their metropolitan leagues and Morgan Strasser had been one of the clubs in talks to join the ISPSL. A few weeks later the U.S. Soccer Football Association (recently renamed from the U.S. Football Association) gave the new league permission to operate and took up an internal discussion about its possible affiliation with the ASL. The league’s affiliation with the ASL never occurred and Wieszmann launched his organization as a fully-independent league. Originally planned to start in April, the league’s season was pushed back to an early June opening. In the interim, the league gained a new club in the newly-organized Detroit Wolverines, and Morgan Strasser and John Inglis were rebranded as the Americanized, Pittsburgh Indians and Toronto Greenbacks respectively.

The Liverpool FC squad that crushed the Maroons in 1946.

On June 2, the Chicago Maroons played an exhibition match against Liverpool FC at Soldier Field and were crushed 3-9. But, while official attendance numbers aren’t known, the crowd may have been large enough to bring new investment into the league. A few days after that match, it was announced that Leslie O’Connor, general manager of the Chicago White Sox, had purchased a half-interest in the Chicago Vikings and that the club’s home grounds would be Comiskey Park.

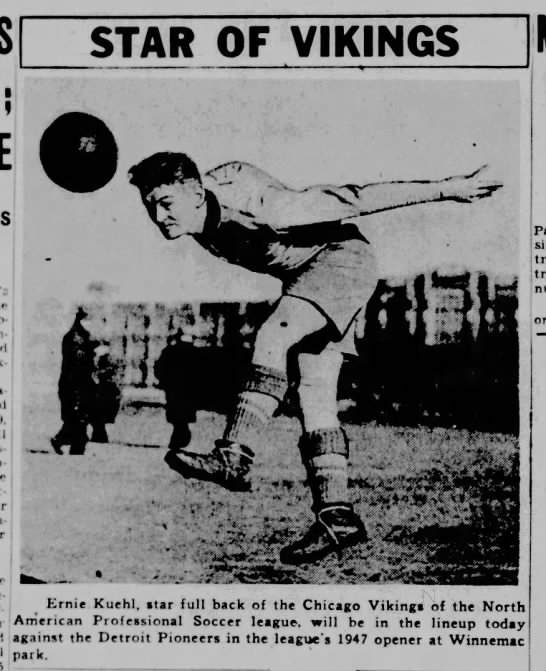

The league began its eight-game home-and-home summer schedule on the weekend of June 6. On opening day, the Chicago Vikings and Detroit Wolverines drew 4-4 at Comiskey Park with center forward, Gil Heron, scoring a hat trick for the Wolverines. Born in Jamaica in 1922, Heron moved to Canada and then the U.S. with his family as a teenager, eventually landing in Detroit. When war broke out, Heron, as a British subject, joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. Following the war he returned to Detroit to work at an auto plant while also playing soccer. In 1945, playing for Venetia in the Detroit District Soccer League, he scored a staggering 44 goals in just 14 games. Recognized as the first black player in a pro U.S. soccer league, Heron continued to shine scoring 15 goals in eight starts. Heron was easily the league’s top offensive star with his goal totals nearly double the next-highest seven scored by Roscoe Anderson of the Vikings, Pete Matevich of the Maroons, and Harry Pitchok of Pittsburgh.

With 11 points, the Wolverines edged out the Greenbacks by one point to take the inaugural season championship. During the season, a post-season playoff series had been planned but was called off.

Although crowds weren’t as large as hoped, attendance was regularly in the 2,000 to 4,000 range and the league was seen as a modest success. In the December meetings, Fred Weiszmann stepped down as President of the league in order to spend more time as general manager of the Maroons. Leslie O’Connor was named president of the league and Weiszmann named vice president. The league received applications from a number of new organizations and set an expansion franchise fee of $5,000. The Detroit Pioneers, a top amateur club, and the newly-organized St. Louis Raiders were admitted to the league on January 27, 1947. In addition, the league approved a split schedule for 1947: a first half in the spring; and a second half in the fall.

April 6, 1947 - Chicago Tribune

But, as the league looked to expand, it also began to contend with a need to tighten their finances. During those same meetings, Martin Donnelly withdrew his champion Detroit Wolverines from at least the first half of the season. Donnelly spent $40,000 (over $500,000 adjusted for inflation) during the 1946 and was unable to field a team in time for the spring session. The last straw for him was an impression that the league was not living up to the promise of being a big league sport. The Wolverines’ franchise was held open pending a decision if Donnelly was going to field a team for the second half. In addition, both Chicago clubs moved out of their major league grounds and decided to share a high school stadium in Winnemac Park. The St. Louis Raiders had initially planned on using a major league venue, Sportsman’s Park, but decided to use the 3,000-seat Public Schools Stadium instead.

One more hit during the off-season caused the league’s future to seem more wobbly than at first glance. The Chicago Tribune published a front-page story which revealed that Fred Weiszmann had signed a number of players as amateurs, but had, in fact, paid them. One of these, Pete Matevich, was being paid $100 per game which made him the highest paid player in the league. In contrast, Gil Heron, the undeniable star of the league on the pitch, was paid $30 dollars per game. Even after being sold by the inactive Wolverines to the Maroons in the off-season he was still only making $5 more.

The Maroons’, and Heron’s, second game of the 1947 season against the Raiders was also the first professional game in St. Louis since the St. Louis Soccer League disbanded in 1938. A newspaper report before the match noted that Heron would be only the third black player ever to appear on a St. Louis soccer field. Half-back, José Leandro Andrade, one of the greatest footballers of his generation and member of the Uruguay world champion squads, visited St. Louis during Nacional’s 1927 U.S. tour. And, top scorer at the 1938 World Cup, Leônidas, played there when his Botafogo squad played two matches against the St. Louis Shamrocks during a 1936 tour of Mexico and the U.S.

Gil Heron

In Chicago, Heron found a bigger venue than Detroit, but also more abuse on and off the field. As the only black player in the league, fans, even those at home, would hurl taunts and racial epithets at him. Opposing players often kicked, pushed and roughed him up. That July Ebony featured Heron in a piece titled the “Babe Ruth of Soccer”, but often injured and harassed, Heron’s play suffered and he only scored four goals in the first half of the 1947 season.

The league’s schedule for that first half called for a 10-game home-and-home series among the clubs beginning in April and running through June. It was another close one with Pittsburgh and Toronto ending the half at 14 points each. Bad weather caused a number of postponements and, with mounting financial difficulties, league officials met in June to discuss whether it was feasible to play the fall schedule. The discussions ended with an understanding that no team would drop out of the league, the Detroit Wolverines would rejoin, and a fall half would be scheduled.

March 22, 1947 - Detroit Free Press (Bottom right corner)

By the end of August things were looking more bleak. A six-game fall schedule was tentatively approved, and play began the first weekend of September. But, when the second half got underway, the Wolverines never returned, the Vikings quit the pro game and the Maroons folded. The Chicago Maroons franchise was transferred to a new club, the Chicago Tornadoes and it was decided that the Tornadoes would get the best players from the Maroons and Vikings. This new club was owned by the men who had previously financed the defunct Maroons, but Fred Weiszmann was not part of the new franchise. As play began, the Detroit Pioneers dropped out before playing their first scheduled league game against Pittsburgh. The league was, for all intents and purposes, down to three active clubs with an additional one attempting to quickly organize.

After a few games for each active club, the league took a pause to play a previously unscheduled best-of-three series to determine the first half champions. Pittsburgh twice beat Toronto 3-2 on October 11 and on October 12 to take the series. The league announced that the playoffs were taking place during a break so the four remaining league teams (the Tornadoes, Indians, Raiders, and Greenbacks) could prepare for a reconfigured second half. But, just over a week later the league declared it was suspending operations and officially declared Pittsburgh the champions. The Tornadoes never played a game and the remaining active clubs (the Vikings, Pioneers, Raiders, Greenbacks, and renamed Morgan Strasser) returned to the amateur ranks.

In postwar United States, the country had emerged as the most powerful country in the world. A new world order was quickly forming with America as the primary bulwark against the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc. The “American way” was no longer just a lifestyle, it was now undeniable proof we were on the right side in the burgeoning Cold War.

The moment the NBA was born. Image courtesy of WBUR.

At the end of three seasons, the BAA merged with the NBL to form the National Basketball Association. The end of the 1949 pro football season saw both major leagues struggling financially. That December, the AAFC effectively merged with the NFL when three of its seven teams, the Cleveland Browns, the San Francisco 49ers, and the Baltimore Colts, were admitted into the older league. Both of these post-war pro leagues have had a major impact on the American sports landscape.

The narrative of the American Dream tells us that, with all things being equal, anything can be achieved through hard work. Through that lens, the league’s collapse can be seen as a failure of league officials and team owners to understand the market for pro soccer in the late 1940s. A failure that would continue to haunt the sport for the next half century with league after league.

But, in retrospect, what if all things weren’t equal? What is the legacy of the NAPSL then? It is a legacy of a sport that is not American enough. It is legacy of a league whose brightest star was too black. A legacy that Americans can be comfortable that soccer is a failure because it is not good enough, and that soccer is not good enough because it is a failure.

Gil Heron played the next few years with amateur clubs Chicago Sparta and Detroit Corinthians. In 1949, his first wife, Bobbie Scott, and he had a son. In 1951, Celtic F.C. toured the U.S. and Heron was invited to an open tryout. He left his wife and young son for Glasgow and, after a trial, and was signed by the club, becoming the first black man to play for the legendary Scottish club. In his debut for the club, he scored two goals in a League Cup match but was released the next year after only a handful of first team appearances. Heron spent then next two years as a journeyman in the UK and eventually returned to Detroit and a new life.

Gil Heron did not meet his first son, Gil Scott-Heron, again until the famous poet, musician and activist was 26 years-old.