The American Pyramid: Alternative Models

Previous pieces in this series touched on the need for a lower Division that would formally oversee a semi-pro/elite amateur level of soccer currently missing from the U.S. pyramid and the barriers travel would create for such system of regional leagues. A further piece touched on the necessity for a partnership among such regional organizations in order to have a stable environment for clubs and leagues to prosper. This piece will bring together the ideas behind those pieces and offer some practical propositions on how to begin to structure the lower tiers of the U.S. soccer pyramid.

The piece that focused on the hurdle of distances between clubs at the regional level argued that the English pyramid doesn’t offer the best blueprint for the U.S. system. Other major European pyramids offer better examples but still don’t have to deal with the physical size of a country as large at the U.S. Better models might be found closer to home.

The Mexican football league system is often overlooked by the average U.S. soccer fan. But the structure of their pyramid can be instructive for ways to organize the U.S. system. The Federación Mexicana de Fútbol Asociación (FMF) administers four levels of professional soccer. The first two levels are fully national professional leagues: Liga MX; and Ascenso MX.

Tier three of the Mexican pyramid is the Liga Premier, also a national professional league. But, the FMF has split Liga Premier into two distinct leagues, Serie A and Serie B, with Serie A being the higher level of competition within the third tier. This tiering within a formal tier allows an additional level of flexibility for leagues and clubs that would be beneficial for the lower tiers of the U.S. pyramid. In addition, each year, the FMF divides Serie A into regional groups to cut down on travel between the teams. While Mexico isn’t quite as large as the U.S., it is possible for a professional club to travel similar distances. For example, the second division, Ascenso MX, currently has teams in Juarez and Cancun. The overland distance between those clubs is 2100 miles, a distance similar to Los Angeles to Chicago.

The fourth tier of the Mexican system is the Liga TDP. It currently consists of over 200 clubs split up into 13 regional groups. The groups function as leagues and the clubs play full home and away schedules within each group. The top clubs from each regional league advance to a playoff tournament for one promotion spot to the third tier. Clubs at this level are lower professional and semi-pro organizations with stadiums seating in the low thousands. The leagues also have relatively small geographical footprints that keep travel to a minimum and engender local rivalries.

One more system that might be helpful to look at is the Brazilian pyramid. An important factor to consider is that Brazil is roughly the same size as the U.S. The Confederação Brasileira de Futebol (CBF) organizes four levels of professional soccer: Série A, B, C and D. Much like Mexico, the top three tiers are national leagues with Série C split into two regional group in order to cut down on travel.

Série D is the formal fourth tier but the format is different due to the interesting nature of Brazilian soccer. Brazil contains two different overlapping pyramids. The first is the national pyramid outlined above, the second is a series of independent state pyramids. Clubs in the national pyramid also play concurrently in state leagues.

Rather than a series of regional leagues, Série D is a large tournament (68 teams in 2018) made up of the best clubs from the state leagues. The first stage are four-club groups played home and away. The following stages are two-legged knockout ties with the final four clubs promoted to Série C. Brazil’s version of a fourth tier also provides an alternative that gives flexibility to a system that isn’t as perfectly hierarchical as the traditional European pyramids.

To avoid confusion the term league when used in an example is meant to mean the grouping of clubs who play each other. An umbrella organization that has “League” in its name but manages league play (the current UPSL and NPSL for example) is not the league for this example. The conferences or divisions within the umbrella organization would be considered the leagues.

In addition, promotion and relegation is the third rail of U.S. soccer commentary. The competitive movement of clubs up or down the soccer pyramid is such a small part of the overall discussion of the U.S. league system. But so much has been invested in the phrase itself that its meaning has lost most of its power to influence. In this piece most of the discussion is focused on how the structure of the pyramid might give the most freedom for clubs to grow and move up (or down) rather than specifics on how to do that via competition.

At its most basic, the main proposal is to simply build the fourth tier Regional League System from the leagues and clubs currently understood to make up the informal Division 4; the NPSL and USL League Two. As of today, the NPSL includes 91 clubs and USL2 includes 72 clubs. A Regional League System of over 160 clubs would mean a robust start while still providing some room for expansion into underserved areas.

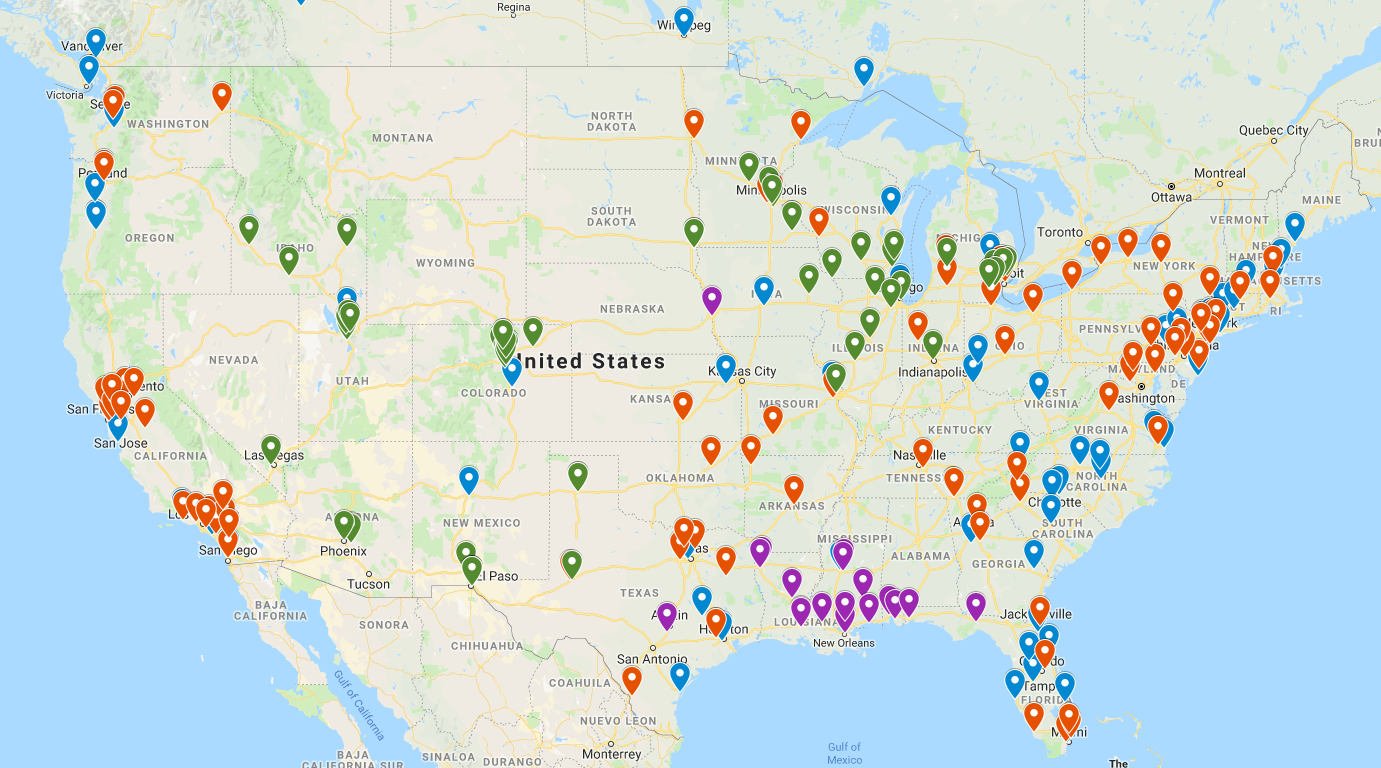

A look at the location of the clubs (NPSL in red and USL2 in blue) shows a good coverage of the country’s major population centers. Though, a few major locations seem to lack the expected number of tier four clubs. The Chicagoland, Denver and Phoenix metro area each only have one “Division 4” club each. Those areas would seem ripe for regional tier four leagues. Also, historically St. Louis was once a major hotbed for U.S. soccer. An honest question: are those days really over or is the area ready for rejuvenation?

Loading in clubs from the UPSL Midwest, Colorado, Southwest and Mountain Conferences (in green) provides a better idea of how those geographical gaps might be partially filled up. In addition, the up-and-coming Gulf Coast Premier League (in purple) shows how the currently-empty Gulf Coast could be covered. While these UPSL & GCPL leagues and clubs may not be able to hit the ground running as tier four operations, formalizing a structure giving them the base to work toward that goal would be beneficial. Administering them as a tier four B league would allow growth toward tier four proper for both individual clubs and the leagues themselves. These groups of clubs are just a few examples and, as there is obviously more ground to cover and many worthwhile grassroots organizations to provide direction in those areas, not nearly the end of this discussion.

A second possible alternative would be a situation where the structure is imposed from above rather than formed at the grassroots. The USSF could be a primary mover for such a scenario but that is an unlikely situation since the federation has shown no interest in managing grassroots soccer. Perhaps a more likely situation would have MLS, in partnership with a lower tier organization, moving in to the grassroots soccer realm in order to create a formal feeder or minor league system. Their interest could push USSF’s involvement into the creation of a formal fourth tier using MLS’ preferred model as its underpinnings. Such a better-resourced endeavor would likely create a winner vs. loser scenario that might leave some of the current leagues and clubs out in the cold.

Could a hybrid using part of the Brazilian model work? In such a version, the leagues would continue to operate independently but provide promotion, either through league results or a separate tournament, to a competition akin to a “regional champions league”. The promotion mechanisms would move teams from those independent leagues into the next season’s RCL that would also take place concurrently with the league season. Rather than the disparate leagues, such a RCL tournament could be the formal tier four and provide better clubs the ability to compete at a higher level.

As it is practically infeasible for a Regional League System to be created and filled wholesale by completely new clubs, any such system will by necessity be made up at its core from teams currently in the NPSL, USL2 and other such leagues. So, it would seem the best option for those organizations and the clubs in them would be to have an agreement between current leagues to form a partnership before a structure is imposed upon them. Having club input on how the creation of this new tier would move forward would also be greatly beneficial to ensure a necessary level of grassroots buy-in and perspective.

Practically though this is difficult to envision as soccer organizations in the U.S. have historically had an antagonistic relationship with each other. This barrier might overcome by the formation of an independent entity that would handle the negotiations between the parties involved while also providing advice and oversight to the process. Once the system is built and running, this entity would continue to oversee and administer the leagues.

This set of articles on the creation of a transitional Division IV in the U.S. soccer pyramid is nowhere near a comprehensive or perfect plan on how to do so. The options put forward and the rationale behind them are presented to hopefully help move forward the discussion of the continued growth of grassroots soccer in this country. We are at an inflection point in the history of the sport where the U.S. finally has a viable Division I league but the lack of direction from above on the local game continues to be sorely lacking. Rather than wait for mandates handed down from on high, it is imperative that the U.S. soccer community takes advantage of this moment and guide it toward a more holistic club- and fan-based version of the sport.

- Dan Creel

Check out the first two articles of this series: Part 1 Part 2